iptables is a management tool for the firewall software netfilter in the Linux kernel. iptables is located in the user space while netfilter is located in the kernel space, where functionalities of firewalling, network address translation (NAT), packet content modification and packet filtering is implemented. Both together are commonly referred to just iptables.

Stateful Packet Inspection

Stateful Inspection is nothing more and nothing less than attempting to ensure that traffic moving through the firewall is legitimate by determining whether or not it’s part of (or related to) an existing, accepted connection.

Netfilter Basics

iptables is made up of threee components: tables, chains and target.

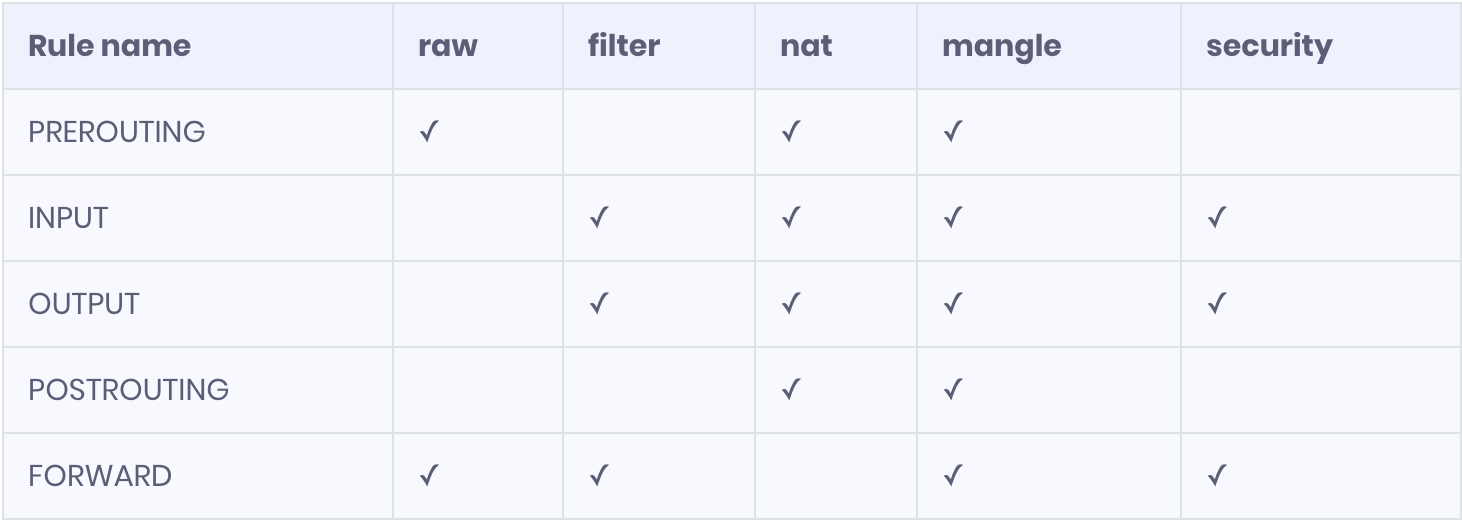

Tables are the major pieces of the packet processing system, and they consist of

- FILTER is used for the standard processing of packets, and it’s the default table if none other is specified.

- NAT is used to rewrite the source and/or destination of packets and/or track connections.

- MANGLE is used to otherwise modify packets, i.e. modifying various portions of a TCP header, etc.

- RAW is used for configuration excemptions.

- SECURITY is used to enforce access control network rules.

Chains are lists of rules within a table, and they are associated with “hook points” on the system, i.e. places where you can intercept traffic and take action. Different “hook points” are:

- PREROUTING: Immediately after being received by an interface.

- POST ROUTING: Right before leaving an interface.

- INPUT: Right before being handed to a local process.

- OUTPUT: Right after being created by a local process.

- FORWARD: For any packets coming in one interface and leaving out another.

Here are the default table/chain combinations:

Targets determine what will happen to a packet within a chain if a match is found with one of its rules. Most common ones are:

- ACCEPT: Firewall will accept the packet.

- DROP: Firewall will drop the packet.

- QUEUE: Firewall will pass the packet to the userspace.

- RETURN: Firewall will stop executing the next set of rules in the current chain for this packet. The control will be returned to the calling chain.

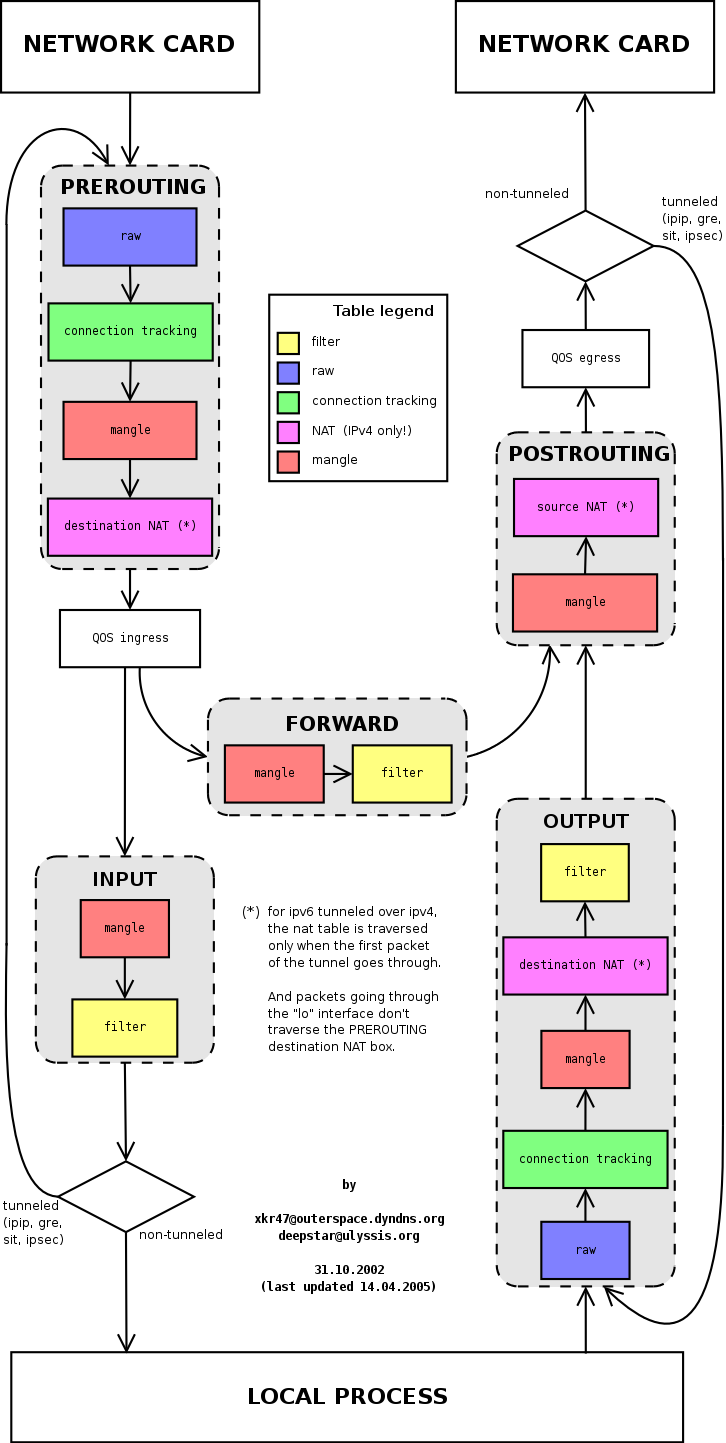

The following figure shows the iptables call chain.

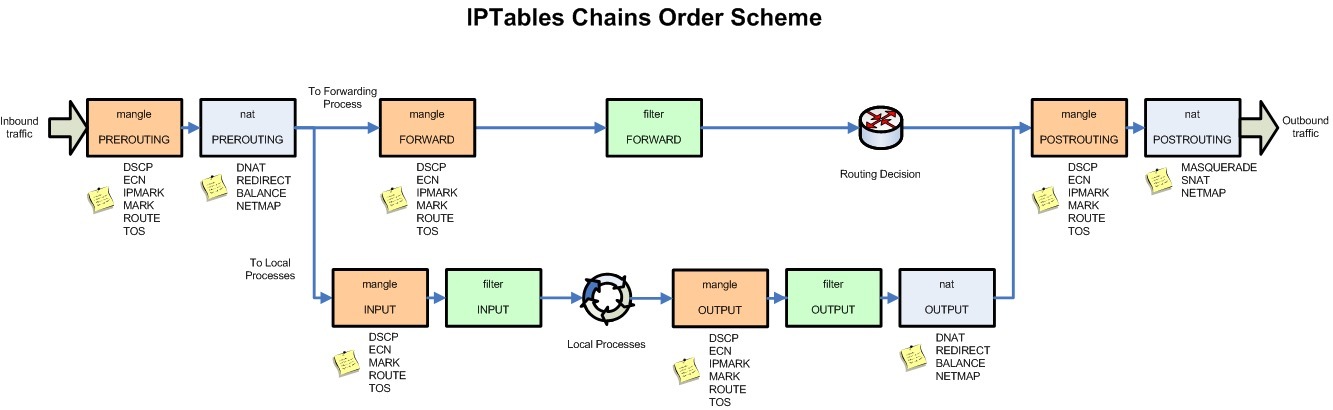

The following figure is the call chain sequence of iptables.

Using iptables

To see all the firewall rules on your system.

# iptables –list

To view the mangle table

# iptables -t mangle --list

To view the nat table

# iptables -t nat --list

To view the raw table

# iptables -t raw --list

If you don’t specify the -t option, it will display the default filter table. So, both of the following commands are the same.

# iptables -t filter --list

or

# iptables --list

Examples:

Some of the examples to understand how iptables are used

Allow Outgoing (Stateful) Web Browsing

iptables -A OUTPUT -o eth0 -p TCP –dport 80 -j ACCEPT

iptables -A INPUT -i eth0 -p TCP -m state –state ESTABLISHED,RELATED –sport 80 -j ACCEPT

First rule is appending a rule to the OUTPUT chain for protocol TCP and destination port 80 to be allowed. It is also specifying that the incoming packets will need to exit the machine over interface eth0 (-o is for “output”) in order to trigger this rule.

The second rule allows the web traffic to come back, without which browsing will not work. The “state” option allows for “stateful” connection. Packets are not able to move through this rule and get back to the client unless they were created via the rule above it, i.e. they have to be part of an established or related connection, and be coming from a source port of 80 — which is usually a web server.

Allowing Outgoing Pings

iptables -A OUTPUT -o eth0 -p icmp –icmp-type echo-request -j ACCEPT

iptables -A INPUT -i eth0 -p icmp –icmp-type echo-reply -j ACCEPT

Here, we’re appending (-A) to the output (OUTPUT) chain, using the icmp (-p) protocol, of type echo-request (–icmp-type echo request), and jumping (-j) to the ACCEPT target. That is for the outgoing packet.

For the return packet, we append to the INPUT chain instead of OUTPUT, and allow echo-reply instead of echo-request. This, of course, means that incoming echo-requests to your box will be dropped, as will outgoing replies.

“Passing Ports” Into A NATd Network

One of the most commonly-used functions of firewall devices is “passing ports” inside to other private, hidden machines on your network running services such as web and mail.

iptables -t nat -A PREROUTING -i eth0 -p tcp -d 1.2.3.4 –dport 25 -j DNAT –to 192.168.0.2:25

Here we are using the nat table here rather than not specifying one. Remember, if nothing is mentioned as far as tables are concerned, we are using the filter table by default. So in this case we’re using the nat table and appending a rule to the PREROUTING chain, which takes effect right after being received by an interface from the outside.

This is where DNAT occurs. This means that destination translation happens before routing. So, we then see that the rule will apply to the TCP protocol for all packets destined for port 25 on the public IP. From there, we jump to the DNAT target (Destination NAT), and “jump to” (–to) our internal IP on port 25. Notice that the syntax of the internal destination is IP:PORT.

Second part of enabling NAT is to configure the rules portion. Below is what is needed to get the traffic through the firewall:

iptables -A FORWARD -i eth0 -o eth1 -p tcp –dport 25 -d 192.168.0.2 -j ACCEPT

In other words, if you just NAT the traffic, it’s not ever going to make it through your firewall; you have to pass it through the rulebase as well. Notice that we’re accepting the packets in from the first interface, and allowing them out the second. Finally, we’re specifying that only traffic to destination port (–dport) 25 (TCP) is allowed — which matches our NAT rule.

The key here is that you need two things in order to pass traffic inside to your hidden servers — NAT and rules.