Sockets are the preferred way of network communication. They are provided by Operating Systems as socket API, which are based on the principles of reading and writing files.

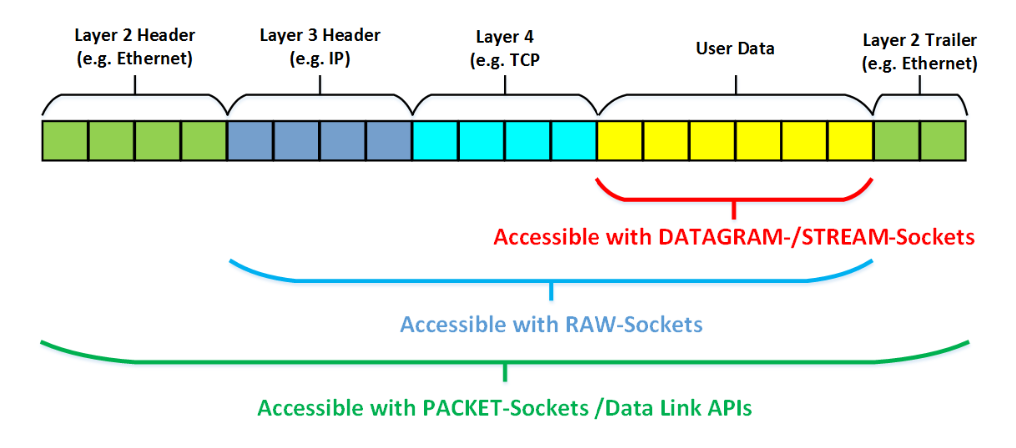

A program gets a socket using OS provided API. Socket API returns a socket descriptor (integer value) similar to the Read and Write Operations on files. This socket descriptor is used to write or read data from the socket. The data written to the socket is encapsulated by the operating system by adding network layer headers and trailers before sending via the network interface to the target host. The received data from the socket is presented to the program without the headers and trailers, only the user data is presented to the user. These sockets are called DATAGRAM-sockets (UDP based) or STREAM-sockets (TCP based) provided via the Berkeley socket API. For these two types of sockets, user is unaware of the communication between the lower layers. The user is only responsible for creating the socket and then providing the data that needs to be sent.

To gain access to the data of the lower layers, there are other options: RAW-sockets, PACKET-sockets, network drivers and Data Link layer APIs. With these APIs it is possible for an application to change and access the fields of the Network layers that are used for sending the data.

TCP Sockets

TCP Socket internals

For each TCP file descriptor tracked by the kernel there is a struct tracking TCP information (e.g. sequence numbers, current window size etc.), as well as a receive buffer and a write buffer.

When a new data packet comes is received by network interface (NIC), kernel is notified either by being interrupted by the NIC, or by polling the NIC for data. The choice of interrupt vs polling mode depends on the network traffic load. A new mechanism using a mix of interrupt and polling mode is provided by NAPI (new API).

When the kernel gets a packet from the NIC it figures out what TCP connection the packet is associated with based on 4-tuples (source IP, source port, destination IP and destination port). This information is used to look up the struct sock in memory associated with the this connection. The packet is copied to socket’s receive buffer in sequence (packet may come out of order). Now, kernel will wake up any processes doing a blocking read, or that are using an I/O multiplexing system call like select or epoll_wait to wait on the socket.

When the userspace process calls read on the file descriptor it causes the kernel to remove the data from its receive buffer, and to copy that data into a buffer supplied to the read system call.

Sending data works similarly. When the application calls write it copies data from the user-supplied buffer into the kernel write queue. Subsequently the kernel will copy the data from the write queue into the NIC and actually send the data. The actual transmission of the data to the NIC could be somewhat delayed from when the user actually calls write(2) if the network is busy, if the TCP send window is full, if there are traffic shaping policies in effect, etc.

One consequence of this design is that the kernel’s receive and write queues can fill up if the application is reading too slowly, or writing too quickly. Therefore the kernel sets a maximum size for the read and write queues. This ensures that poorly behaved applications use a bounded amount of memory.

A similar technique is used to limit the amount of kernel memory reserved for new connections. A newly established TCP connections are created by calling accept(2) on a listen socket. A listen socket is one that has been designated as such using the listen system call.

The prototype for listen takes a socket file descriptor and a backlog parameter:

int listen(int sockfd, int backlog);

The backlog is a parameter that controls how much memory the kernel will reserve for new connections, when the user is not calling accept fast enough.

Example:

UDP Sockets

Example:

RAW Sockets

RAW Socket allows the user to access and manipulate the header and trailer information of the lower layers. Since RAW-sockets are part of the Internet socket API they can only be used to generate and receive IP-Packets.

Following items still have to be observed:

- RAW-sockets requires root access permissions.

- The ports of the network layer are not endpoints anymore since RAW-sockets work on the layers below.

- The

bind()andconnect()functions are no longer necessary. A RAW socket can be bound to a network device using SO_BINDTODEVICE. - The

listen()andaccept()functions are without function, since the client-Server-Semantic is no longer present. When we use RAW Sockets we are sending unconnected packets. - IP headers of RAW sockets can be manually created by the programmer if the option IP_HDRINCL is enabled. If IP_HDRINCL is not enabled the IP header will be generated automatically.

- When a RAW socket is created, any IP based protocol can be specified. This results in a socket only receiving messages of the type of the specified protocol.

- When creating a RAW-socket, IPPROTO_RAW protocol can be specified to indicate that the headers will be created manually. This way he can send any IP based protocol. However this socket is not able to receive any IP packets, to receive all IP based packets a PACKET Socket has to be used.

Example:

PACKET Sockets

PACKET-sockets are a special type of RAW-sockets that allow access to the fields of the Data Link Layer. To use them there are some definitions required that not part of the socket-API, but are provided by the Linux Kernel.

Restrictions similar to the RAW-sockets have to be considered:

- PACKET Sockets requires root access permission.

- The ports of the Network layer are not endpoints anymore, since RAW Sockets work on the layers below.

- The

bind()andconnect()functions are no longer necessary.bind()can still be used to define the interface over which the Data Link Layer packet should be sent. - The

listen()andaccept()functions are of no use since the Client-Server-Semantic is no longer present. When we use RAW-sockets we are sending unconnected packets.

Debugging Sockets

Find the dropped packets in raw sockets

Packets dropped could be seen from netstat, ethtool outputs. For UDP packet drops check output of netstat -us. Packets are also dropped at NIC layer itself, which could be seen via ethtool -S <device_name>

Try using larger buffer space(SO_RCVBUF) and increase system wide maximum via sysctl control net.core.rmem_max

At NIC layer, try increasing ring buffers to handle bursty traffic.

You can retrieve the total number of received packets and the number of dropped packets in your program using PACKET_STATISTICS socket option as described in the packet(7) manpage.

#include <linux/if_packet.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

...

struct tpacket_stats lStats = {};

socklen_t lStatsLength = sizeof( lStats );

if ( getsockopt( mRawSocket, SOL_PACKET, PACKET_STATISTICS, &lStats, &lStatsLength ) == 0 )

{

printf( "Total Packets: %u\nDropped Packets: %u\n", lStats.tp_packets, lStats.tp_drops );

}

else

{

perror( "Failed to get network receive statistics" );

}