eBPF stands for extended Berkeley Packet Filter but officially referred to as BPF. BPF was intially developed for high performance packet capture in 1992. In recent years (2012 - 2014), BPF is rewritten to a general purpose virtual machine that can be used for many things like networking, monitoring, security and performance analysis.

BPF is a register-based Virtual Machine (VM) using a custom 64-bit RISC instruction set capable of running Just-In-Time native-compiled BPF programs inside the Linux kernel with access to a subset of kernel functions and memory. This VM is part of the mainline kernel, so it doesn’t require any 3rd party modules.

By design, virtual machine and its programs are restrictive:

- No loops are allowed, so each BPF program is guaranteed to finish and not hang.

- All memory access is bounded and type-checked.

- No null dereferences.

- Program must have at most BPF_MAXINSNS instructions.

- The “main” function takes a single argument (the context).

The VM was also exposed to userspace via the bpf() syscall and uapi/linux/bpf.h

Work flow

BPF programs are run by the kernel when events occur, so they can be viewed as a form of event driven programming. Events can be generated from kprobes/uprobes, tracepoints, dtrace probes, sockets and more. This allows to hook and inspect memory in any function at any instruction in both kernel and user processes, to intercept file operations, inspect specific network packets and so on.

An event triggers the execution of an attached BPF program which then can store information in maps, print to ringbuffers or call a subset of kernel functions defined by a special API. An BPF program can be attached to multiple events and different BPF programs can also access the same map to share data.

Steps for running an BPF program:

- Userspace sends bytecode to the kernel together with a program type which determines what kernel areas can be accessed.

- The kernel runs a verifier on the bytecode to make sure the program is safe to run (kernel/bpf/verifier.c).

- The kernel JiT-compiles the bytecode to native code and inserts it in (or attaches to) the specified code location.

- The inserted code writes data to ringbuffers or generic key-value maps.

- Userspace reads the result values from the shared maps or ringbuffers.

The map and ringbuffer structures are managed by the kernel independently of the hooked BPF or user programs accessing them. Accesses are asynchronous via file descriptors and reference counting ensures structures exist as long as there is at least one program accessing them. The hooked JiT-compiled native code usually gets removed when the user process which loaded it terminates, though in some cases it can still continue beyond the loading-process lifespan.

To ease writing BPF programs and avoid doing raw bpf() syscalls, the kernel provides a convenient libbpf library containing syscall function wrappers like bpf_load_program and structure definitions like bpf_map.

How to use BPF

To understand how the various userspace tools work, let’s define the high-level components of an BPF program:

- The backend: This is the BPF bytecode loaded and running in the kernel. It writes data to the kernel map and ringbuffer data structures.

- The loader: This loads the bytecode backend into the kernel. Usually the bytecode gets automatically unloaded by the kernel when its loader process terminates.

- The frontend: This reads data (written by the backend) from the data structures and shows it to the user.

- The data structures: These are the means of communication between backends and frontends. They are maps and ringbuffers managed by the kernel, accesible via file descriptors and created before a backend gets loaded. They continue to exist until no more backends or frontends read or write to them.

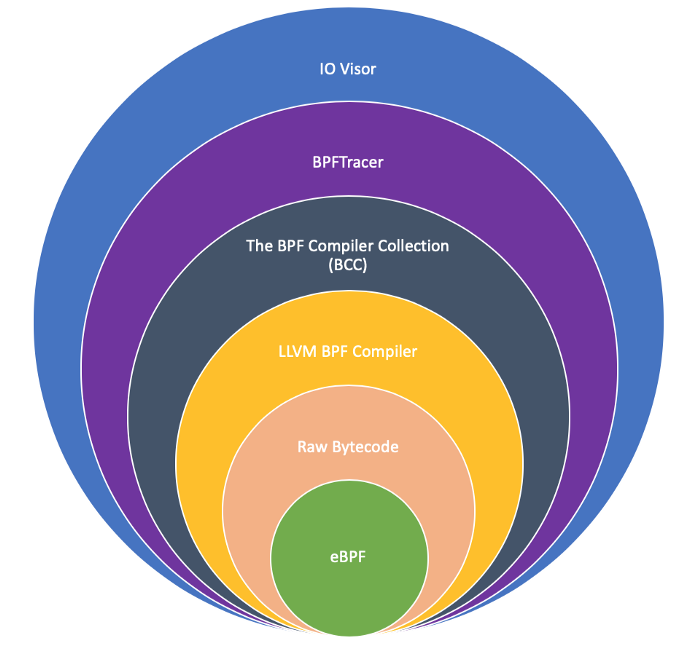

There are several ways to write the program to use BPF.

- Raw Bytecode

- LLVM BPF Compiler

- The BPF Compiler Collection (BCC)

- BPFTracer

- IO Visor

Raw Bytecode

Raw Bytecode is the least user-friendly but most efficient way to program BPF. It does not need any userspace tools. Kernel tree BPF examples contain raw bytecode or load pre-assembled bytecode files via libbpf. We can see this in sock_example.c, a simple userspace program using BPF to count how many TCP, UDP and ICMP protocol packets are received on the loopback interface.

The LLVM BPF compiler

As writing raw bytescode is hard and error prone, a module capable of compiling the LLVM intermediate representation to BPF was developed. This allows some higher-level languages like C, Go or Rust to be compiled to BPF. The most developed and popular is based on C as the kernel is also written in C, making it easier to reuse existing kernel headers.

LLVM compiles a “restricted C” languege (no unbounded loops, max 4096 instructions and so on ) to ELF object files containing special sections which get loaded in the kernel using libraries like libbpf, built on top of the bpf() syscall. This design effectively splits the backend definition from the loader and frontend because the BPF bytecode lives in its own ELF file.

The BPF Compiler Collection (BCC)

BCC solves the problem that not everyone has kernel sources at hand, which are needed by LLVM BPF Compiler. BCC provides an easy-to-use framework for writing, loading and running BPF programs, by writing simple python or lua scripts in addition to the “restricted C”.

The BCC project has two parts:

- The compiler collection (BCC proper): This is the framework used for writing BCC tools.

- BCC-tools: A constantly growing set of well tested BPF-based programs ready for use with examples and manpages.

BCC arranges BPF program components like this:

- Backends and data structures: Written in “restricted C”. Can be in separate files or stored as multiline strings directly inside the loader/frontend scripts for convenience.

- Loaders and frontends: Written in very simple high-level python/lua scripts.

BCC focuses developer attention on writing frontends without having to wory about lower level details. The BCC install footprint is big. It can easily take hundreds of mb of space which is not very good for small embedded devices which can also benefit from BPF powers.

BPFTracer

For cases, where BCC is also too low-level, BPFTracer was built on top of BCC providing an even-higher abstraction level via a domain-specific language inspired by AWK and C.

What BPFtrace does by abstracting so much logic in a powerful and safe (but still limited compared to BCC) languege is quite amazing. This shell one-liner counts how many syscalls each user process does.

bpftrace -e 'tracepoint:raw_syscalls:sys_enter { @[pid, comm] = count(); }'

IOVisor

IOVisor is a Linux Foundation collaborative project built around the BPF VM and tools. It uses some very high-level buzzword-heavy concepts like “Universal Input/Output” focused on marketing the BPF technology to Cloud / Data Center developers and users:

- The in-kernel BPF VM becomes the “IO Visor Runtime Engine”

- The compiler backends become “IO Visor Compiler backends”

- BPF programs in general are renamed to “IO modules”

- Specific BPF programs implementing packet filters become “IO data-plane modules/components”

The IOVisor project created the Hover framework, also called the “IO Modules Manager”, which is a userspace deamon for managing BPF programs (or IO Modules), capable of pushing and pulling IO modules to the cloud, similar to how Docker daemon publishes/fetches images. It provides a CLI, web-REST interface and also has a fancy web UI. Significant parts of Hover are written in Go so, in addition to the normal BCC dependencies, it also depends on a Go installation, making it big and unsuitable for the small embedded devices

IOVisor is actually BPF in the cloud.

#Getting out of Insomnia As BPF gains functionality and growth, the inability to block is increasingly getting in the way. The patch set from Alexei Starovoitov adds a new flag, BPF_F_SLEEPABLE, that can be used when loading BPF programs into the kernel; it marks programs that may sleep during their execution.

This is work in progress and something to keep an eye on.